|

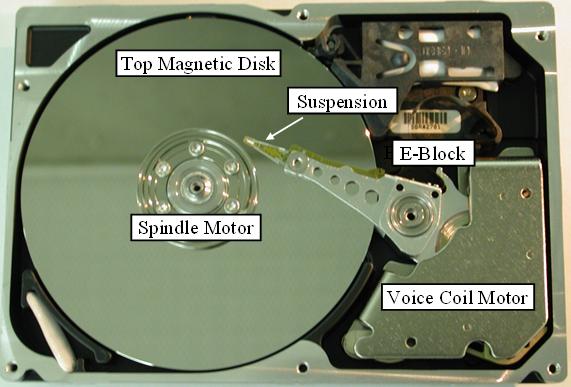

Hard Disk Drives How does a hard disk drive (HDD) work? A very basic explanation is that a recording head applies a magnetic field to a disk changing the bits of information on the disk as it rotates. The head can then read the information as it “flies” over these bits. Some of the components of a HDD are labeled below.

The spindle motor typically rotates the disk at 7200 RPM, and the suspension move across the disk to write on or read certain areas of the disk. The animation below shows how the suspension moves. Click on the image to see animation. Tribology comes into play as a result of the interaction between the recording head and the disk. In order for HDD capacity to keep increasing, the distance between the head and disk (flying height) needs to be lower than 5 nm. At this distance adhesion plays a large role, and the head has a greater chance of contacting the disk, a very undesirable but inevitable occurrence in the presence of shock loading. In order for the head to maintain a certain distance above the disk, it is shaped in such a way that there is a pressure build beneath it, much like an airplane wing. Shown below is an illustration of a head-disk interface (HDI) and animation of the head response to roughness.

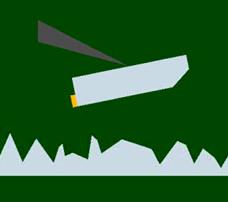

Illustration of the various components and dynamics at the HDI Click on the image to see an animation of the head-disk interaction. The gold portion is the recording sensor. Note that the roughness and pitch movement of the slider are exaggerated. The flying height of a HDD is becoming smaller in order to achieve higher data densities. Currently, the maximum density is about 100 Gbit/in2, or about 3000 songs in one square inch, and the goal is to reach 1 Tbit/in2, or about 30,000 songs in one square inch. There are many sizes of HDD’s in production. The smallest HDD, a microdrive, has a 1” disk and is commonly used in digital cameras, MP3 players, and is gaining acceptance in cellular phones. To see a video showing the components and assembly of a microdrive click here. |